Change is one of the constants in human existence.

Often developments and innovation bring advantages and ease (witness the

washing machine and how it has transformed housework,

| Thor Washing Machine advertisement 1909 (1st know ad for an electric washing machine) |

or the creation of the

battery and our resultant dependence on it within our increasingly mobile world).

|

| Voltaic Pile - 1st battery, invented by Volta in 1800 (in response to Galvani's twitching frog leg) |

However, for many the arrival of new approaches, often imposed upon them

without consultation or choice, is uncomfortable and difficult. Guatemala, and in particular the religions and

beliefs of its people, is an interesting case study in coping with change.

From the earliest days of the Conquistadors, Guatemalan

people have developed ways of combining their traditional beliefs with religions and attitudes introduced by others.

|

| Mayans dressed as Conquistadors Festival of Santo Tomas, Chichicastenango, Guatemala |

When the Spaniards arrived, along with suppression,

disease and destruction, they brought Roman Catholicism. It was perhaps

reassuring to the Mayans to see the worship focused on a cross (admittedly one

with a longer arm pointing to the south.) The Mayans have a symbolic cross,

linked to their creation story and understanding of the universe.

|

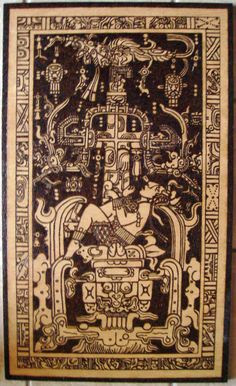

| Mayan Cross as an altar From Tomb of Lord Pacal, Mexico |

They believe

that, after a few false attempts (using animals, wet clay and wood), the first

men were moulded out of maize flour mixed with blood. The Mayan mythology maintains that the Mayan

people themselves were made out of all colours of corn – white for their bones, yellow for

the flesh, black for their hair and eyes and red for blood.

|

| Different coloured maize |

There are four colours

of maize (or sweetcorn/corn as we refer to it in the UK) – red, black, white

and yellow - these correspond to the colours of people. White is for the people

of the north, yellow is for the communities of the south, black represents the inhabitants to the west and the Mayans themselves believe

that they are red and that their direction is the east, with its close link to

the sun.

|

| Ceramic lid of an incense censer, depicting King Pakal falling into the jaws of the underworld, below a Mayan Cross symbolising the Tree of Life, Mexico |

The Mayan cross, in use long before the arrival of

Christianity, illustrates these directional differences (as well as a green centre for growth and development) and it is considered to be a

depiction of the tree of life drawn

from Mayan cosmology. Mayan astronomers and shamen believed that the centre of

the world was the centre of the universe (and for many Lake Atitlan is the

world’s centre, where creation began, with mountains rising up from the primordial

waters to create the lake – interesting to note that the lake is in fact the

giant crater of a volcano erupted 85 million years ago that has filled with water of the millennia, before

being surrounded by volcanoes itself).

|

| Lake Atitlán just after dawn |

Looking at the star-studded sky at night,

especially in parts of Yucatán where there is little light pollution, you can

see the Milky Way with ease – there is a large dark area near its centre.

Drawing lines to the north, south, east and west, you create a cosmic cross

with the earth at its heart and a link to significant objects in the night sky.

The Mayan knowledge of astronomy and mathematics was lost on the Spanish

invaders, but the power of worship for both communities was intense.

|

| Mayan women selling flowers for worship on the steps Chichicastenango, Guatemala |

The Spanish catholic missionaries and

representatives of the Church were careful to place their churches and

cathedrals on traditional religious sites, where Mayans had worshiped for

centuries. In return, when ordered to build churches, especially on established

Mayan sacred sites, the Mayans would secretly include some of their own customs

and practice, such as a flight of 18 steps leading up to the main church in

Santiago Atitlán (18 is the number of months in a year according to the

traditional Mayan religious calendar), followed by a second flight of 20 steps (that

represent the number of days in each month).

|

| 2nd flight of steps, built by Mayans, leading to Santiago Atitlán |

In many locations Mayan practices have been allowed

to continue or to blend with the in-coming Roman Catholic approach, to enable

an acceptable co-existence. St John the Baptist is (for obvious reasons)

associated with water – even now it is hard to tell when a Mayan prays in front

of an alter to St. John the Baptist whether the prayers are to him or actually to the

traditional god of water, the rain god Chac. Mayan prayers often involve

offerings, such as rum to purify, or flower petals to sweeten the message.

|

| Mayan women selling flower petals to sweeten prayers Chichicastenango, Guatemala |

In

addition to physical offerings, Mayans almost always use candles, which are equally common in Roman Catholic

churches and an essential act to accompany prayers, especially for the souls of

the dead. There are many such areas of overlap, or “synchronicity” as the locals call

it. Although Roman Catholic candles are

traditionally white, Mayan candles are symbolic and more vibrant than their Catholic

counterparts – various colours are used to represent different requests (green

candles, linked to the planet Mercury, are supposed to bring good business deals, influence over a

loved one, hope, employment opportunities and lottery wins – they are also

believed to overcome bad influences; black candles are associated with Jupiter

and are used to incapacitate enemies and prevent unwelcome gossip but they need to be used

with care as they can backfire on the user; red is the colour of the East and is used for energy, love and the

reduction of sadness and bad energies;

|

| Mayan prayer candles in a chapel in Chichicastenegro |

white candles are linked to purification and aid memory and calm anxiety

as well as being used to protect children; yellow, the colour of the south is

energy-giving and encourages good health; pale blue is often used to support

students, as it is linked with mental capacity, but is also good for travellers

and those in need of money; dark blue is the colour of fortune; and purple

candles have traditionally been used to dispel bad thoughts and defeat

illness). The Roman Catholic churches that we have visited in Guatemala have all allowed the

use of multi-coloured candles as part of local prayer.

Recently the Mayans have become more overt – when

the Roman Catholic church in Santiago Atitlan was destroyed in the severe

earthquake of 1960, fragments were stored and the then parish priest, an

American named Father Rother (more of him in another post), commissioned local

artisans to build a new altar and screen.

Certain carvings have been added to

the decorations, ones that one would not normally expect to see in a Roman

Catholic cathedral. With a high degree of freedom the wood carvers and

craftsmen (two brothers - Diego Chavez Petzey and his younger brother Nicholás

Chavez Sojuel) included significant Mayan imagery: like a Christian triptych

there are three parts to the altars at Santiago Atitlan – to the Mayans the

triple altars within the church represent the three volcanoes that overlook the lake and the main

altar is clearly shaped like a mountain. On the main screen, to the the right hand

side there is an image of St John the Baptist walking up the exterior,

but on the left there is a Mayan Sharman replicating his pose.

There are local caves

used for worship up in the hills surrounding lake Atitlán, particularly the

hill that is thought to resemble the head of a sleeping Mayan,

and it is

probable that the image of the shamen reminds Mayan worshipers of trips into

the hills to pay respects to ancestors, elders and ancient gods. An interesting

piece written

by Allen J. Christenson describes the Chavez brothers’ influences and inspiration and

provides explanations for some of the carvings. Traditional Mayan images

abound – the Quetzal (the symbol of Guatemala, the name for the local currency

and a sacred but living bird) is shown on the pulpit,

either giving or

receiving the Holy Word. Perhaps most surprising of all is the inclusion of

Maximón (pronounced Ma-shi-mon in the local dialect), a local folk saint, amongst the saints and

biblical figures carved on the altar, he can clearly be seen in a panel which

also depicts a traditional deer dance.

Maximón is an interesting character – in many ways

he is the badass boy of sainthood. Stories vary as to his identity – by turns he

is considered Satan, a saint (referred to as San Simon), Judas, or a relic of

pre-colonial Mayan religion. An elderly man standing near the shrine we visited

simply stated that he is a friend of the saints. We were fortunate in that we

were taken to meet him in person. He sits between two guards in a smoke-filled,

candlelit room that reeks of rum and Quetzalteca , the local hooch.

Dressed in slightly antiquated Western attire, wearing a stetson and a

surprising number of ties, he looks a little as though he might be suffering

from toothache - a handkerchief is tied round his face and under his chin. He

sits silently, observing while he chomps on a cigar.

He is a carved effigy and

the simple wooden mask is reputed to conceal his actual face (we were told that

it is carved of fine jade, but that Gringos are not allowed to see it, due to

the first mask having been stolen by the Spanish and the replacement purloined

by a priest in 1950’s, who donated the jade mask to a French museum – it was

only returned in the late 1970’s). Maximón’s current visible mask is said to be

the fourth carved since the original theft – it is made from Tsaj’tol tree wood

(the wood which gave from to the wooden beings of the second creation in Mayan

legend).

|

| Mayan Jade Mask, 600 AD |

Maximón is viewed as a badly behaved but socially-concerned

grandfather for the people; providing protection and granting wishes and at

times playing tricks. He resides with a local clan for a year before relocating

in Holy Week – the new host home being elected by the group of 12 brotherhoods

or “cofradias” (which are family-based clans in distinct neighbourhoods,

established by the Spanish to aid town governance). Due to the complexity of

Maximón’s reputation – a mixture of benevolence with occasional mischievousness

and even malevolence, people are loathe to relinquish worshiping him, just in

case he takes the desertion personally and decides to be vindictive. It’s

better to be safe than sorry.

Roman Catholicism, combined with traditional Mayan

beliefs has been the dominant religion in Guatemala until the late 21st

century. However, evangelical churches started coming, to provide aid and to

establish missions, after the 1978 earthquake. Currently 40% of the rural

population have converted to evangelical churches. We flew in from Dallas with

a group of 23 from a US church who were going to Guatemala for a week to build

houses for the rural communities.

|

| Evangelical mission to Guatemala from St Luke's Church, 2013 |

In exchange for converting and agreeing to

donate 10% of their annual income (a traditional tithe) a native Mayan can

receive a new house and potentially a better standard of living. Superficially

this seems a good deal, but how does it work when the majority of the rural

communities and many of the urban-based indigenous people still follow the old

beliefs?

|

| Mayan mask depicting a rising soul emerging from the Jaguar's jaws |

The answer is “synchronicity” – in effect hedging your bets by

entwining beliefs or practicing obeisance to both (but perhaps being more open

about one than the other, so as not to risk losing your new home). Corruption

is rife in Guatemala (from the top downwards: the past vice president’s

secretary was exposed

for corrupt conduct by the UN and the deputy standing with the preferred

candidate, Baldizón, in September’s elections has just been accused of money

laundering, thereby potentially knocking them both out of the running). Hence

people do not expect the government to make their lives easier – it is more

probable that prayers will bring prosperity.

|

| Wherever we went in Guatemala Baldizón hung over us like and ever watching god - an inescapable influence in rural pastures or in towns |

In this complex, often immoral and demanding

environment apparent duplicity is simple and an effective way of coping with

change – utilising a subtle combination of the old with the new. Some activity

is perhaps just deception for personal gain, but this is ingrained in the national

psyche – after all, Maximón himself was/is tricky to deal with and encourages tricksters.

|

| Small effigies of Maximón for sale in Santiago Atitlán shops - mouths agape for cigarettes |

No comments:

Post a Comment